symphony no. 4, “HEICHALOS”

Duration ca. 20'

3(3d/picc).3(3d/eh).3(3d/bass cl).2+1cb)/ 4.3.3.(3 on bass trombone)/1 timp + 2/hp/pf/str

View Score

LISTEN

Commissioned by the Nashville Symphony Orchestra, Giancarlo Guerrero, Music Director.

Premiered by the Nashville Symphony Orchestra, Giancarlo Guerrero, Music Director, March 22-24, 2018.

Other performances: Nashville Symphony Orchestra conducted by Giancarlo Guerrero, May 31-June 3, 2019

Nashville Public Radio: Composer Jonathan Leshnoff on Jewish Spirituality, Tenacity and Writing for the Violins of Hope

“Speaking about the symphony, he sees ‘the Violins of Hope as the physical embodiment of Jewish survival…’ No wonder, then, that the breathtaking twenty-two-minute work should assume the character of a wrenching meditation. Don't let its prosaic movement titles fool you either: as titles, “Fast” and “Slow” might seem like afterthoughts, but the material itself is hardly lacking in profundity.”

—Textura, June 2019

PROGRAM NOTE

The Symphony No. 4’s subtitle, “Heichalos,” provides the key to this spiritual dimension, which in turn shapes the formal design of the 20-minute composition.

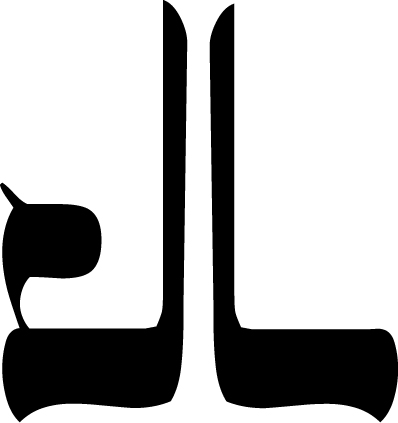

Heichalos (usually spelled Heichalot in the Hebrew literature) literally refers to “rooms” and is one of the oldest written mystical works. Leshnoff was specifically inspired by the Heichalot Rabbati (also known as Heichalos Rabbasai). According to the composer, this is an “ancient Jewish mystical text written approximately 2,000 years ago. It is one of a few texts that explicitly describes the way to attain a mystical encounter with the higher worlds. Through the means outlined in the text, the initiate meditates himself into ‘rooms’ (in Hebrew, heicalos) where he advances, room by room, to a communion with the Divine. The Rabbis who were qualified to teach and attempt this type of meditation have long ago ceased to walk the face of this Earth.”

Leshnoff describes Symphony No. 4 as “a musical depiction of the initiate’s travels through these rooms.” The music proceeds in two parts of roughly equal lengths, each about ten minutes. These should not be thought of as “movements” in the usual sense, he points out, because the two parts contrast so powerfully and have such distinctive characters, though on a motivic level they are connected by the arresting theme stated majestically at the outset (a sequence of fortissimo chords spread across the orchestra).

Part One refers to the opening and a later chapter of the Heichalos text: “When one enters the [first] room, he knows everything that will happen in the terrestrial world...when he is on a higher level, he sees each person's secret deeds...when he is on yet a higher level, he is separated from mankind; anyone who tries to harm him is rebuked by a Heavenly tribunal...and when he approaches the seventh room, the angelic Chayos glare at him each with their 512 eyes, each stare like a flash of lightning.” The overall character of the music here, says Leshnoff, is of a darker hue than anything he had hitherto written, though there is a foretaste in his Second Symphony. Taking up images that were disturbing and frightening in a spiritual way, the composer deploys thick orchestration, using a very dark brush. “This does not have the lightness and nuanced touch of my other works. I’m purposefully using mysterious and foreboding orchestration,” he adds.

In stark contrast to the darkness and speed of Part One is Part Two, which Leshnoff characterizes as “a love song between humanity and God,” its language therefore much warmer. There’s a lot more nuance and detail, which you can hear in just the string writing, with the added sonorities of harp, bass clarinet, and vibraphones. The audience should feel as if suddenly they have been pushed from one extreme to the other. For Part Two, Leshnoff’s score appends brief quotes from Chapter 28 of the Heichalos text, which glorifies various qualities of “the One who lives forever” (“might and faithfulness,” “understanding and blessing,” and the like).

It is in Part Two that the Violins of Hope come into the foreground: in the first five minutes or so, the strings alone play extended, slow, quasi-Mahlerian lines, and following a massive climax for full orchestra and organ later in the movement, they again take center stage at the end (with discrete accompaniment from vibraphone, piano, and harp). Into the score the composer has written brief thought-inducing questions: “who do you love?” and “where are they now?” at the beginning and end, respectively, of Part Two.

Leshnoff explains that he has been exploring how to make “the transitions from music to enter into spiritual realms.” Thus, the start of Part Two is a measure of notated rest with these questions held as long as the conductor is inclined. “I want the musicians to meditate on that phrase and to start thinking about who they love. Then, at the end, what has happened to them — are they dead or alive, part of your life?”